By Heather Hahn

May 12, 2020 | UM News

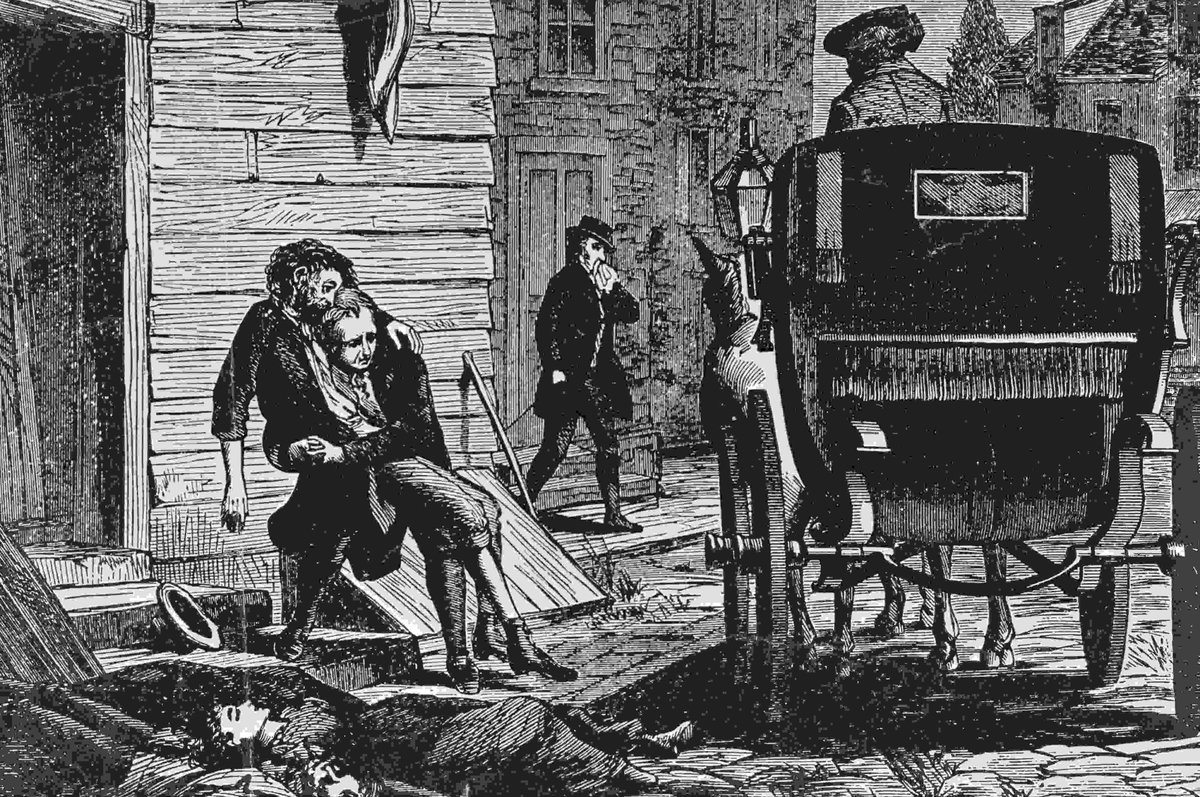

Artist interpretation of the yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia in 1793. As the virus sickened thousands, a U.S. founding father turned to two Methodists for help. Print from Bettmann Archives.

The spread of a mysterious deadly disease emptied city streets and filled hospital beds.

Many risking their lives to help were people previously overlooked or even belittled.

Sound familiar?

The year was 1793, and yellow fever was ravaging Philadelphia — then the U.S. capital and the young nation’s largest city.

On a much smaller scale, the epidemic presented similar challenges to the COVID-19 pandemic. And just like now, church leaders found new ways to respond.

Two frontline heroes who stepped up to provide care were African American Methodist leaders — Richard Allen and Absalom Jones.

The two men wrote that “it was our duty to do all the good that we could to our suffering fellow mortals.”

They were acting “true to their Methodist convictions,” the historian Anna Louise Bates recounts in the April issue of Methodist History. Her essay, “Give Glory to God before He Cause Darkness,” details how Methodists including Allen and Jones responded to Philadelphia’s yellow fever outbreaks in the late 18th century.

Both men ultimately became pioneering leaders of new U.S. denominations. But in 1793, the two were licensed Methodist lay preachers, and their city was in trouble.

That August, the virus started sickening thousands in the bustling port city. Fear and financial hardship followed.

By the end of September, some 20,000 citizens had fled the city for safety. They included President George Washington, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and other U.S. government officials. The federal government basically ground to a halt.

However, most of Philadelphia’s residents remained, particularly those not affluent enough to move.

Dr. Benjamin Rush, a prominent Philadelphia physician and signer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, declared the city had an epidemic and turned to Allen and Jones for help.